Malt 101

The Four Elements: Malt

The chemistry trick that makes beer possible!

Have you ever wondered where the alcohol in beer comes from? It doesn’t just appear during the brewing process—it is created by yeast during the fermentation. Specifically, it’s created as a byproduct when yeast consumes sugars. So where does the sugar come from? Malt!

Fun Fact

Barley malt is the most common type of malt used in brewing, but other types of grain can be malted too, including oats, wheat, rye, and even corn!

Malt is a cereal grain that has been sprouted and then dried. This process—called malting—has been done by humans for thousands of years and is what makes beer possible. By triggering the growth of the grain and then halting it, important enzymes are preserved that are necessary in the brewing process. Remember that yeast needs to eat sugars to create alcohol, but the grain is full of starch, not sugar. Brewers convert the grain’s starch into sugar during the mash, and in order to do so, alpha- and beta-amylase enzymes need to be present. Malt types can be characterized by how much of their saccharification enzymes are left, called a malt’s diastatic power. Malts that have high diastatic power have plenty of enzymes available to its own starch to sugar. Let’s follow the path that barley takes through the malting process to see how malt impacts beer flavor!

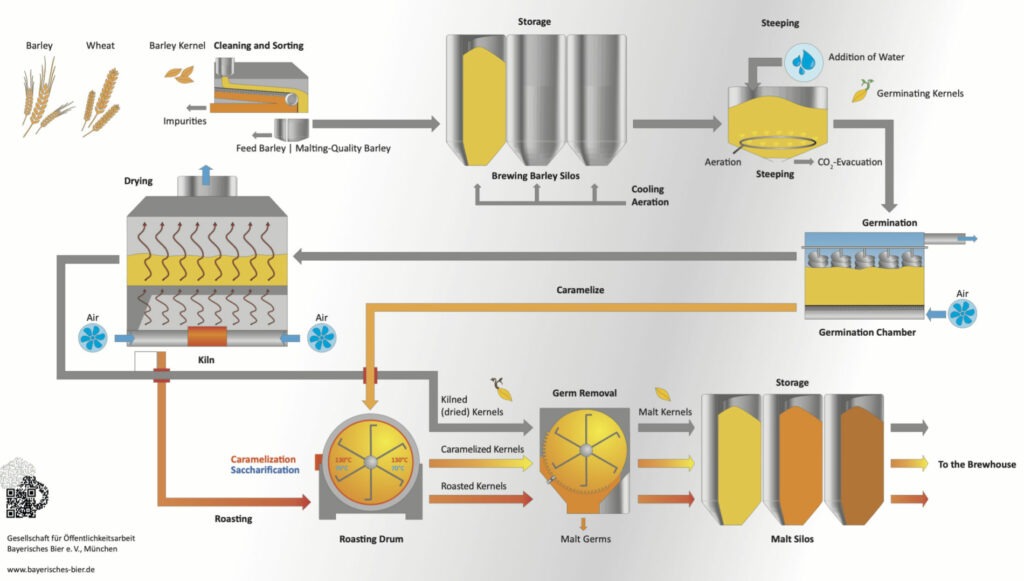

After barley is harvested, it’s transported to a malt house where it can be processed. After sorting the grain and rejecting small kernels, debris, and other unwanted material, the grain is then repeatedly steeped and drained. This triggers the sprouting process within the grain, which leads to a number of different physiological changes. During this period, the grain accumulates the enzymes that are needed during the mash, in addition to sugars and other important wort components. Once the sprouting process has progressed far enough, it is stopped immediately. Letting it continue would lead to the growth of a new barley plant instead of a concentrated packet of enzymes, starch, and sugar!

To halt the sprouting process, the malt is kilned. In this step, the malt is dried with warm air, driving out all the water and preserving the state of the grain. The temperature and time that the malt is dried determines its color and flavor, with lighter malts dried at a lower temperature and darker malts roasted at a much higher one. Now let’s dig into the different types of malt and how they’re used in a recipe!

Types of Malt

1. Base Malt

Base malts are the foundation of any beer recipe. These malts are kilned gently, giving them a pale color. The lower temperatures preserve the enzymes in the grain so that they’re still available to convert starch to sugar in the mash, and will have a high diastatic power. Some base malts even have enough diastatic power to convert starches from other unmalted grains like corn and rice. On their own, base malts usually have cracker or biscuit flavors and will often make up the majority of the malt bill.

2. Highly-Kilned Malts

Kilned malts are produced in the same way base malts are but are exposed to higher temperatures in the kiln during drying. These elevated temperatures create bready, cookie, or honey flavors without completely destroying the enzymes in the grain. These types of malt are great for boosting the malt backbone of a beer without being as sweet as caramel and crystal malts. However, these malts will have a lower diastatic power than base malts since some of the enzymes are destroyed in the process.

3. Caramel and Crystal Malts

Caramel and crystal malts, also called “stewed” malts, are roasted at higher temperatures while still wet from the malting process. These conditions cause enzymatic conversion of the starch to sugar in each kernel, which crystallizes on the surface of the grain. These malts provide longer-chain sugars like dextrins, which yeasts cannot consume and will remain in the beer. In addition, the caramelized sugars can provide a fruity note to the finished beer. These malts are frequently used in the British brewing tradition and are at home in English ales.

4. Roasted Malts

Roasted malts are exposed to the highest temperatures on the malting spectrum. After drying in the kiln like base malts would be, these malts are roasted above 400 F, which creates intense chocolatey, coffee, and toasty flavors. These malts contribute incredible amounts of color to the wort, and are often used in stouts, porters, and other dark beers.

Using Malts in a Recipe

When it is time to brew, brewers often use multiple types of malt in one recipe – though they don’t have to! Choosing the right malts to use is all about finding a balance between what each malt variety can bring. Finding recipes online is a great way to learn how each type of malt is used in different styles, but a good rule of thumb is to start with a quality base malt and add in specialty malts to bring certain desired flavors, like breadiness in a Märzen or coffee/chocolate flavors in a stout. Another thing to keep in mind when choosing malts is how they’ll affect the mouthfeel of the final beer. Base malts with little protein can make very crisp, light beers, whereas adding malts like Vienna malt (a highly-kilned malt) or caramel malts can provide more body to make a fuller beer. Adjuncts can also be a great way to amp up a beer’s body, but we’ll save adjuncts for their own article!

Beer style guidelines, like those published by the Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) or the Brewer’s Association, can be great resources for recipe development. These guidelines are used to judge beer competitions, and provide a set of expectations for beer styles from around the world. In addition, the BJCP guidelines will often have descriptions of typical recipes, like this excerpt from the entry for Witbier: “Unmalted wheat (30-60%), the remainder low color barley malt. Some versions use up to 5-10% raw oats or other unmalted cereal grains.” These guidelines are great places to start when experimenting with different styles.

No matter what kind of beer you’re making, there’s a malt out there to help you craft the perfect flavor. The world’s best beers are all about the balance between the ingredients they’re made from, and malt is a very significant component. The flavors from malt, hops, water, and yeast must balance each other, even in beer styles where one of the elements may take a backseat to the another. Whichever malts you choose, experiment and brew with confidence! The only limit is your imagination.