Hops 101

The Four Elements: Hops

All about the star of the IPA show!

Picture this: you’re sitting at your favorite brewery with a friend drinking a beer after work. You’ve got a West Coast IPA: bright, bitter, piney, and resinous. Your friend has a New England IPA: hazy, juicy, citrussy, and fruity. Hops are responsible for both of these excellent flavor profiles, but how can they be so different? Let’s dive into the world of hops and find out!

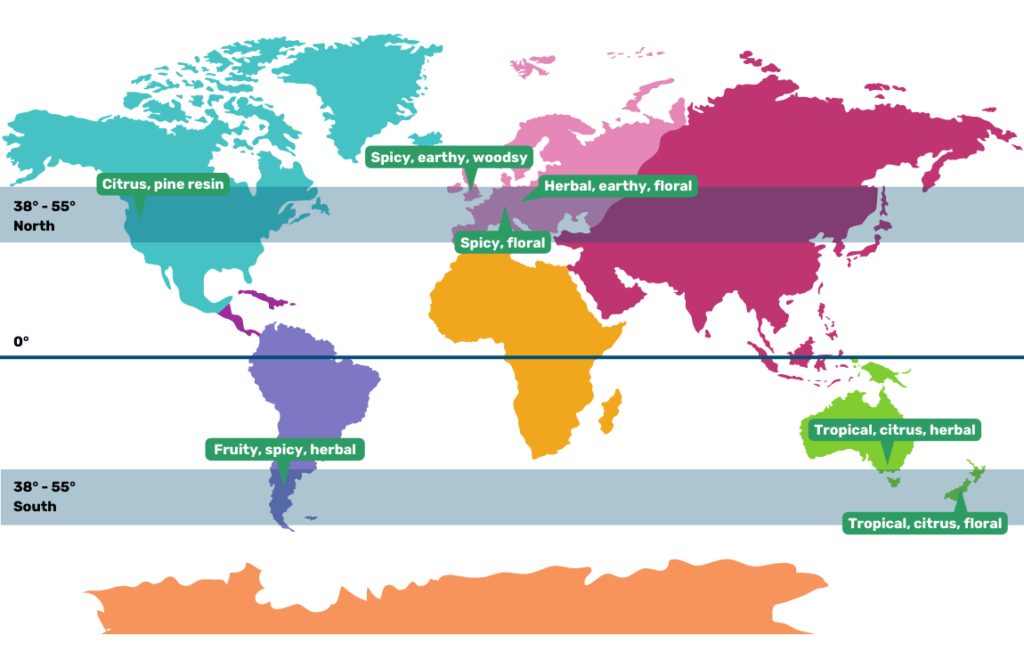

Hops are the flowers of the Common Hop, Humulus lupulus, a climbing plant native to Europe, West Asia, and America. Hop plants grow best between 38- and 55-degrees latitude in full sun, with the major hop growing regions in Northern and Central Europe, the Pacific Northwest, and southern regions like Argentina, New Zealand, and Australia.

Fun Fact

Humulus lupulus is in the same family of plants as cannabis: Cannabaceae!

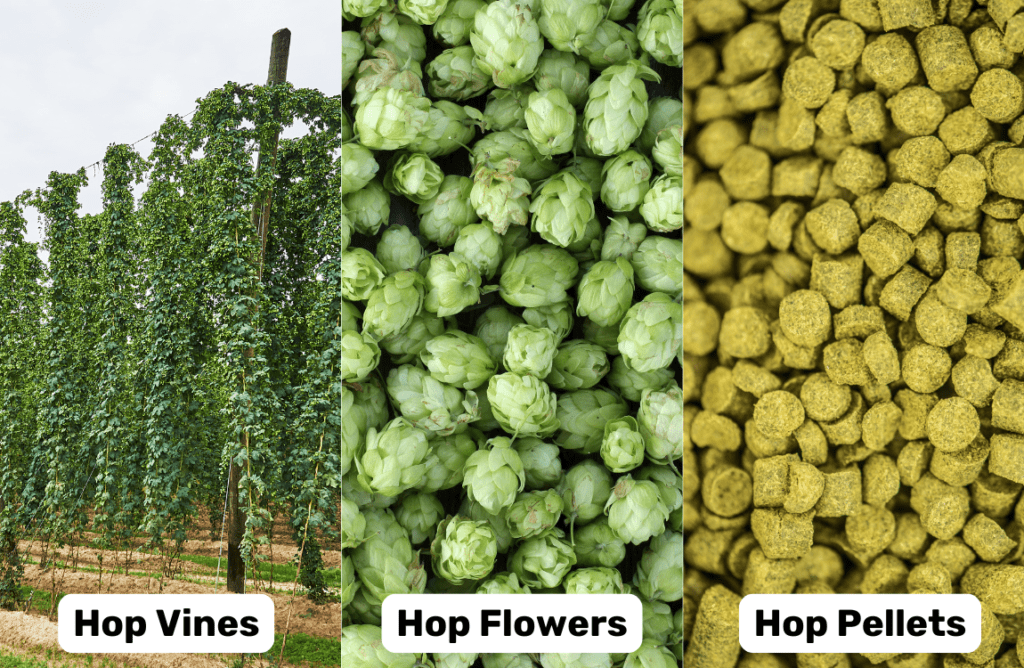

Used for hundreds of years in brewing, hops contain all their flavorful resins and essential oils in their lupulin glands, which are located at the base of the bracteoles in each hop flower. After harvest, hop flowers are dried gently and pelletized: compressed and packed into dense pellets called T90 pellets for storage and use in brewing. However, nowadays, other hop products exist including various kinds of solid and liquid hop extracts.

Fun Fact

Although hops reign now, they weren’t always universally used in beer. Gruit, a mixture of herbs and botanicals, were instead used as a bittering and flavoring agent. German brewers began to switch to hops around 1100 CE, but brewers in England resisted the use of hops in beer until around the 17th century!

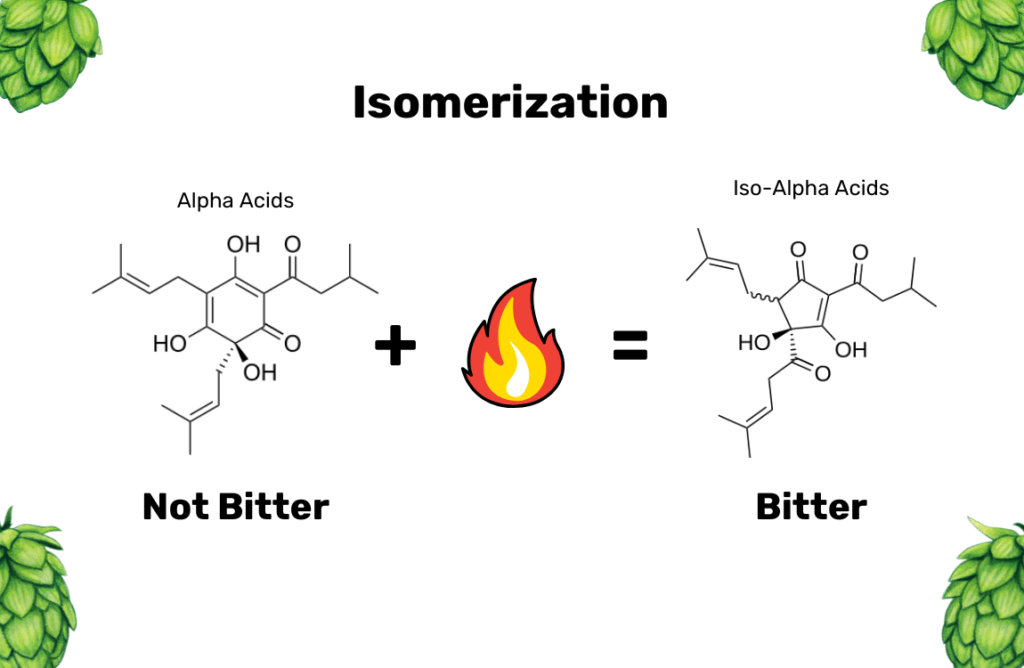

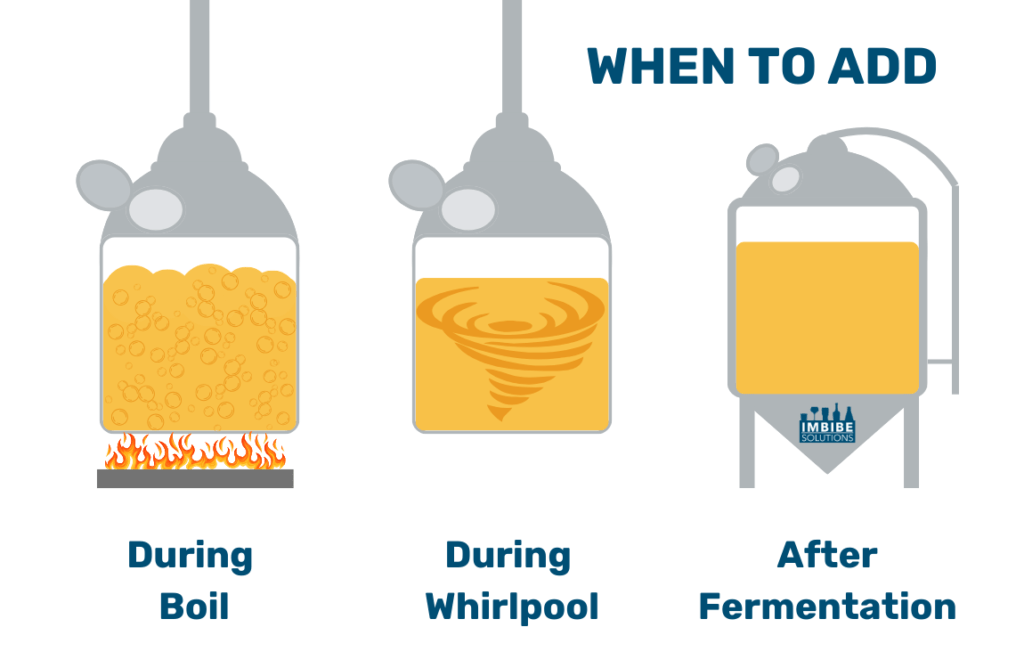

Two major classes of chemicals are responsible for hop bitterness and flavor: hop acids and essential oils. Hop acids, mostly made up of alpha and beta acids, are responsible for the bittering power of hops. Alpha acids are the more powerful bittering agents, and in the hop plant exist as humulone, ad-humulone, and co-humulone. But there’s a catch: these compounds aren’t actually bitter! During the boil, they’re converted to their iso- forms: iso-humulone, iso-ad-humulone, and iso-co-humulone. These compounds, on the other hand, are very bitter. In order for these compounds to convert, they need temperature and time, which is why bittering hops are added early in the boil so that the bitterness can be extracted. Put them in too late in the boil, and their bittering potential is lost.

Essential oils, on the other hand, have the opposite problem: these compounds exist fully formed in the hop plant and are responsible for all of their delicate, fruity, and spicy aromas. Take a whiff of a handful of fresh hops and you’ll see what I mean! These compounds are volatile, however, and high temperatures will drive them out of solution. In order to preserve hop aromas, brewers can add hops into the whirlpool after the boil is complete, where they won’t be lost as quickly. Brewers can also “dry-hop,” or add hops directly to the fermenter, a common practice for all types of IPA.

Let’s go back to our West Coast IPA vs New England IPA example. How should we choose different hops for each of these beers? Thankfully, hop growers provide information about their hops that can help guide our process: they provide alpha-acid values and total oil values, in addition to all kinds of flavor descriptors. West Coast IPA is much more bitter than New England IPA, so we’ll use more bittering hops early in the boil for that beer. We’ll want to select a hop like Magnum, which has a high alpha-acid content around 10-14 percent. In addition, we’ll choose an aroma hop with a resinous, piney character such as Chinook or Centennial.

Fun Fact

Hop bitterness is measured using International Bitterness Units (IBU). One IBU is equivalent to a concentration of 1 mg/L of iso-alpha-acid in solution. The IBU value of a given beer can give you an idea of how much hop acids made it into the final product, but perceived bitterness depends on other factors. For example, a 35 IBU Czech Premium Pale Lager might taste more bitter than a 35 IBU Sweet Stout, since the bitterness in the Stout will be hidden by the extra sugars in the beer.

For the New England IPA, we’ll use either a smaller bittering hop charge or none at all during the boil. For a fruity profile, we could choose Citra, which has characteristics of citrus and mango. No matter which hops we choose, we’ll choose mostly aroma hops for the New England IPA which can be used in the whirlpool or in the fermenter.

What about other styles? Hops are universally used in modern beer, so everything from a Belgian Wit to an Irish stout will have some sort of flavor component from hops. For most old world styles, bitterness is restrained compared to American styles like a West Coast IPA. Regardless, hops still play a crucial role in the style characteristics. German beer just wouldn’t be the same without the familiar earthy and herbal notes that German hops provide.

There is a ton of active research and development on hop genetics and breeding, and new hop varieties are being released all the time. New strains may be more resistant to pests, provide greater yields, or have new, unique aromas. Many new strains are also categorized as dual-use hops, having both a high alpha-acid composition and a high oil content with good aroma. For example, Azacca® has an alpha-acid composition of 14-16 percent and is described as having a tropical fruit and citrus aroma.

With so many different varieties of hops, the possibilities are truly endless. Whether you’re making a bright, bitter West Coast IPA with the hops front and center, or a smooth malty stout with them in the back seat, we can thank hops for the beer bitterness and flavor we know and love.