Decoction Mashing

Long-lost brewing wisdom or antiquated tradition?

Ever been to your local bottle shop and seen beers advertised as double- or triple-decocted? What’s that all about? Some secret German beer magic perhaps? In actuality, it’s a traditional method of mashing developed to tackle historical brewing challenges. So how does it work? Decoction mashing is a type of step-mashing that involves removing, boiling, and adding back a portion of the mash to bring up the temperature of the batch. Typically this is done two or three times, making the beers “double-decocted” or “triple-decocted.” At each step, around 20-40% of the mash is removed and boiled in the boil kettle, then added back to the mash tun. As you might expect, this process takes up a lot of energy and time. Using a decoction mash strategy can take your mash from one hour to up to five or six!

So why do it? Historically, it was used in Germany and Austria for two major reasons. First, the malts they were using were not well modified, and therefore required more processing in the brewhouse to achieve the desired amount of starch extraction. The second reason is a bit more simple: they didn’t have thermometers! Without a reliable way to determine the temperature of the mash, it would have been difficult to hit the target mash temperatures by heating the whole batch at once. Let’s get into each of these reasons in more detail.

The Malt Modification Problem

The malting industry has come a long way since the eighteenth century. Thanks to modern malting technology, today’s malt is very well modified, meaning its protein matrix and cell wall material is thoroughly degraded. This means that the brewer doesn’t have to worry about breaking down the malt in the brewhouse—all that needs to be done is to extract the starches and convert them into sugars. Back when the decoction mashing strategy was developed, malt was nowhere near as good as it is today. (The science of malting has come a long way.) Its protein matrix and cell wall material was left somewhat intact and required additional processing to get the most extract. The distinct temperature steps involved in the decoction mash process is what breaks down these components, allowing access to the starches. In addition, the physical agitation from boiling each decoction portion helps to further break down the malt.

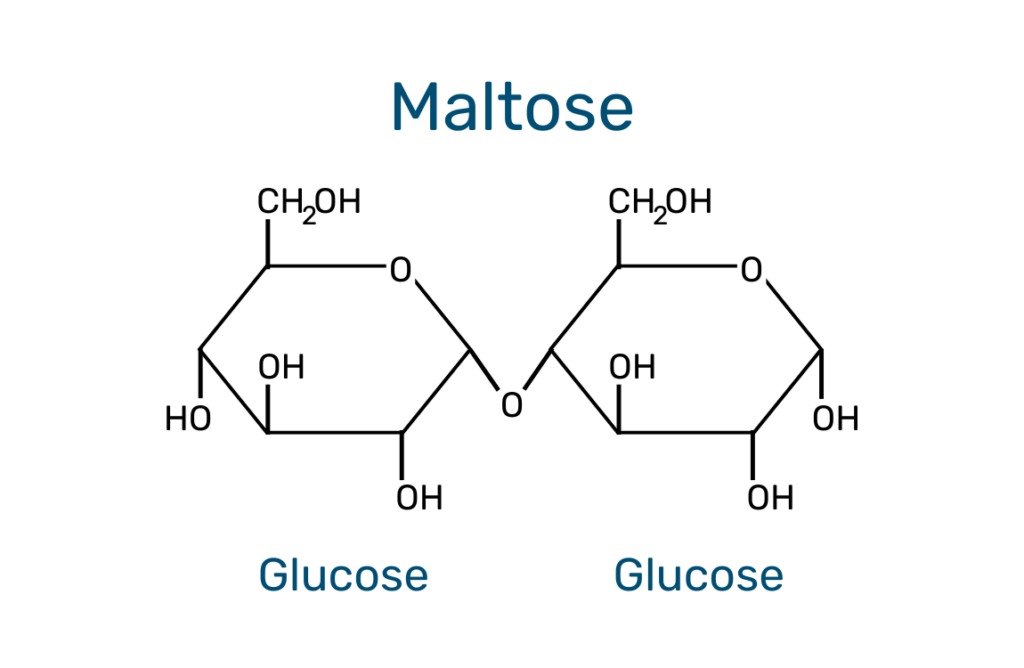

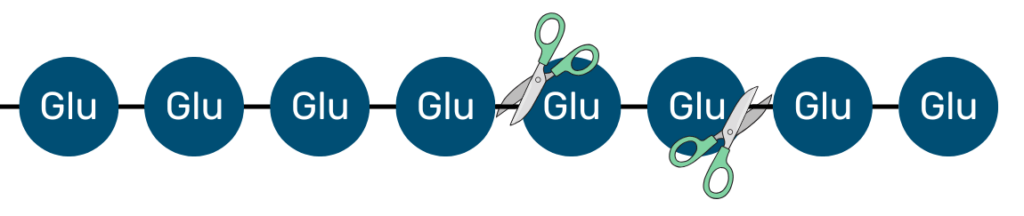

We know today that each of the enzymes active in the mashing process has an ideal temperature at which it is most active. For example, beta-amylase, which chops maltose units off of the end of a starch molecule, is most active around 131-149°F (55-65°C) and alpha-amylase, which cuts larger starch chains into larger sugar molecules, is most active around 140-158°F (60-70°C). There are other enzymes that help break down the malt as well, all of which prefer temperatures lower than alpha- or beta-amylase, but these are the two major enzymes brewers are concerned with in the brewhouse. Therefore, to deal with an undermodified malt, it is important to move through distinct temperature steps to break down the protein matrix before activating the amylase enzymes at 149°F. Below is an example of what these steps might look like:

- Acid Rest: 95-113°F (35-45°C) for 15-20 minutes

- Protein Rest: 115-130°F (45-55°C) for 15-20 minutes

- Conversion Rest: 149-158°F (65-70°C) for 30-60 minutes

From “How to Brew” by John J. Palmer, 2017.

The Temperature Problem

It’s fairly straightforward to hit each of these steps with a modern, mechanized mash tun, and many brewers still use some kind of stepped mash process to increase foam retention. But this brings us to our second major reason that traditional decoction mashing was developed: they couldn’t measure the temperature of the mash! Without knowing exactly what temperature the mash was at, brewers could still bring the mash through each of the distinct steps using the decoction method. By boiling and returning a certain volume of the mash, brewers had a repeatable, measurable process to add heat energy to the process. In this way, they could make the most of their undermodified malt and extract and convert all the starch they possibly could.

So why use a decoction mash today? After all, we have well-modified malt and thermometers. Modern malt really only needs a single infusion mash to achieve maximum extraction, and even if step mashing is desired, modern mash tuns have heating elements which eliminate the need to pump portions of the mash back and forth. According to some, decoction mashing brings out unique malt flavors and aromas you can’t get any other way. There’s some evidence for this, too: by boiling portions of the mash, Maillard reactions create additional compounds that contribute color and flavor to the beer. In addition, decoction mashing can reduce wort pH: wort produced from a decoction mash was around 0.10-0.15 pH lower than the same recipe mashed using a single infusion strategy. For some breweries, it all comes down to tradition: they’ve been decoction mashing since the 19th century and are sticking to their tried and true methods.

Ultimately, it’s up to the brewer to decide if decoction mashing is worth the added time and energy—and up to the consumer to decide if double- or triple-decocting improves the taste and aroma of the beer. Regardless, we’re lucky to have such a variety of brews to try, including decocted ones. So next time you try that double-decocted doppelbock, see if you can taste the magic!