Diacetyl

Brew Better Beer by Busting Butter Bombs!

Ever tasted butter in your IPA? Unless you’re drinking a butterbeer from Hogsmeade, it’s not exactly a pleasant flavor to detect in your brew. But where does that flavor come from, and what does that have to do with movie theater popcorn? Let’s dive into the chemistry and find out!

The Science of Diacetyl

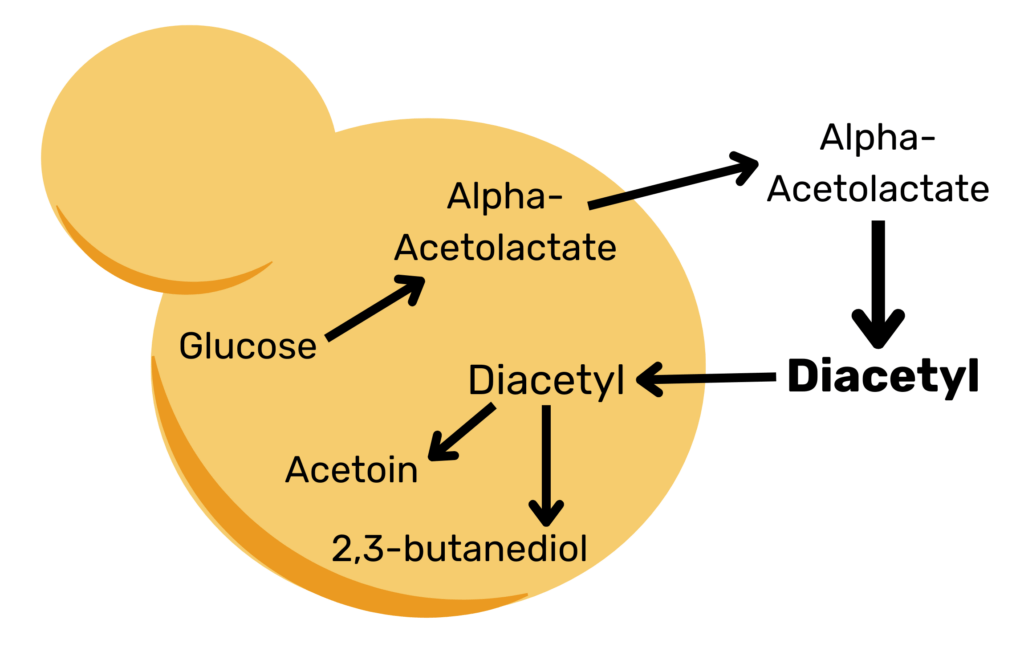

Diacetyl, also known as 2,3-butanedione, is a byproduct of yeast metabolism with a very low sensory threshold and a strong buttery aroma. In beer, elevated levels of diacetyl are considered an off-flavor and are generally unwelcome in the final product. Diacetyl and a simThe Brewing Processilar compound, 2,3-pentanedione, are often referred to as Vicinal Diketones (VDKs) because they both have two ketone groups right next to each other on a carbon backbone. These VDK compounds are produced by yeast strains as they synthesize amino acids in the cell. Glucose is converted to α-acetolactate, which exits the cell and degrades into diacetyl. However, given enough time, the yeast can reuptake diacetyl and process it into acetoin and 2,3-butanediol, which don’t have a significant flavor impact.

Fun Fact

Diacetyl is a major flavor compound present in butter and has such a powerful buttery flavor that it has been used as a butter flavoring in movie theater popcorn!

Because diacetyl is such a powerful off-flavor, it’s important to keep it out of the finished product as much as possible. Good strategies for eliminating diacetyl start with good data. The American Society of Brewing Chemists (ASBC) outlines a few different methods for VDK measurement in method Beer-25 that brewers can use to monitor the levels in their beer. The most accessible method is a spectrophotometric method, and a more precise method using gas chromatography is described as well. An important benefit of both of these methods is that they convert all of the precursor compounds into diacetyl during the analysis. This means that brewers can measure the total amount of diacetyl their product could have, as opposed to how much diacetyl it has at a given point in time. Regardless of the method used, the diacetyl content of a finished beer should be below the taste threshold, which is 0.15 ppm (mg/L).

Brewers can measure the total amount of diacetyl their product could have, as opposed to how much diacetyl it has at a given point in time.

Diacetyl During Production

So how can brewers keep unwanted diacetyl out of their brews? Towards the end of fermentation, many brewers perform a “diacetyl rest” or “D-rest” where they bump up the temperature of the tank so that the yeast can more quickly process the excess diacetyl. In addition, this gives more time for excess α-acetolactate to convert into diacetyl and then acetoin so that it doesn’t degrade later on after the beer has been packaged. VDK is measured during the diacetyl rest, and once levels drop below an acceptable amount, the tank can be crashed, the yeast can be removed, and the beer can move to the next step in production. If a diacetyl rest was not performed, and the tank was crashed as soon as the gravity stopped dropping, the yeast would not be able to ‘clean up’ this excess diacetyl and a significant amount could be left in the beer, giving it that slick, buttery taste.

Fun Fact

Although any amount of diacetyl is considered a flaw in most beers, a bit of diacetyl is acceptable in English, Irish, Scottish styles according to the BJCP and BA style guidelines. This is because English yeast is so flocculent that it falls out of solution before it cleans up all the diacetyl, leading to higher amounts in the finished beer.

Diacetyl rests are a reliable way to eliminate the diacetyl in fermenting beer, but they can cause delays in the production schedule and can be challenging to work around when dry hopping. Luckily, brewers have a few other options to try if diacetyl is a consistent production problem. First, a few different companies manufacture an enzyme called α-acetolactate decarboxylase (ALDC) that converts α-acetolactate directly to acetoin before it can degrade into diacetyl. By dosing a fermentation with this enzyme, diacetyl production is avoided entirely, and a diacetyl rest isn’t required. In addition, some yeast labs have released strains that produce the ALDC enzyme inside the cell, eliminating the need for brewers to add it separately!

Fun Fact

In addition to the normal production of diacetyl by yeast during fermentation, elevated levels of diacetyl in a finished beer can also be a sign of bacterial infection. For example, Pediococcus species can produce diacetyl and are a common beer spoilage organism.

No matter what method brewers use, having an established and repeatable process for diacetyl reduction is key to making excellent beer. Although it requires some extra production steps, testing for diacetyl is a critical quality control step and your customers will thank you for it!