It’s Getting Hot in Here, So Let the Fermentations Go!

What do all craft fermenters have in common? They can use temperature as a tool to reach their stylistic goals. Sure, some yeast prefer specific temperature ranges, but where in that range a producer chooses to work will notably alter the final product. Yeast, in general, thrive between 77-90°F (25-32°C), happily reproducing and multiplying in population. (Party time!)

As the temperature gets colder, the yeast metabolism starts to slow down, sugar is consumed less quickly, and fewer byproducts are produced. Under 40°F (4°C) many yeast start to go dormant.

As the temperature gets warmer, the enzymes within the yeast cells start working faster and byproducts may be converted into new compounds (for good or bad). Once the temperature gets over 95°F (35°C) the yeast cell starts to get stressed out which means mutations may occur and/or undesirable compounds like higher alcohols, esters, and off-flavors may start to be produced. At 140°F (60°C) the yeast cell will die. ☹

While 77-90°F is ideal for yeast growth, we find most fermentations occur at temperatures significantly lower than that. That’s because we aren’t just interested in yeast growth, we are interested in fermentation! Fermentation requires an anaerobic environment (lack of oxygen) that forces the yeast into alcohol and CO2 production, among many other byproducts. By lowering the temperature, we can control the rate of production and, in some cases, prevent catalyzation that might remove or alter desirable compounds.

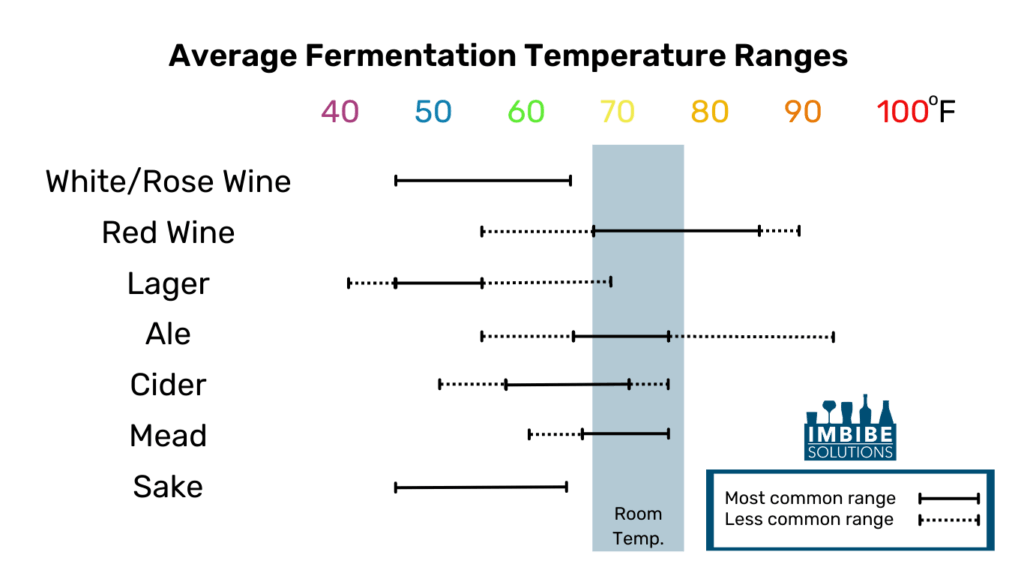

The average fermentation temperature varies depending on the final product being produced and the qualities the producer is trying to feature. From the chart above, you can see that products generally considered as lighter, crisper, and more refreshing are usually fermented at temperatures closer to 50-60°F (10-15.5°C). Products like white wines, lagers, and sakes tend to be cleaner with more raw material characteristics than fermentation characteristics. Once you get above 60°F (15.5°C), you start to see more esters being produced and retained – often delicate fruity and floral flavors and aromas which are distinct features of ciders, some sakes, and some white and rose wines. Perfect for summer!

Products that go through warmer fermentations (room temperature and above) often display more body, structure, and color than their cooler fermented counterparts*. Red wines, ales, and meads extract and retain ‘heavier’ flavor/aroma attributes that aren’t as ‘light’, volatile, or sensitive to catalytic reactions. These may come across as stone fruit esters, spicy flavors, or tannins, among many other characteristics.

*Since beer isn’t fermented on its raw materials the way other products are, this doesn’t necessarily apply. Instead, the body, structure, and color of a beer come from the wort production process.

Fun Fact

Warmer fermentations are faster at converting sugars to alcohol, CO2, and flavor/aroma compounds. The enzymes within the yeast cells have a higher activity at making the magic happen. While this can be beneficial for many styles, it is also more likely that off-flavors may be produced – so be careful! Compounds such as acetaldehyde (bruised green apple or nuttiness), diacetyl (butterscotch or popcorn butter), fusel alcohols, and isoamyl acetate (banana Runts) can be produced in excess at higher temperatures.

Sometimes, starting and ending fermentation temperatures vary. For example, lowering the temperature during the last few days of fermentation in order to retain more volatile flavor compounds. In other situations, the temperature just remains the same throughout – and that is ok too.

Controlling the temperature can change the outcome of a final product. Want your ale to have more yeast characteristics? Ferment it at a slightly warmer temperature. Want your cider to retain more fruity esters? Ferment is at a slightly cooler temperature. This is where the science and art of fermentation intersect, so have fun with it!

Featured image from Paul Mueller Company. Caption is our own.