Wine Aging: Finding that Perfect Balance

I know what you’re probably wondering. Why bother aging wine when you could drink it right then and there? To put it simply, because it is worth the wait. So, what exactly happens during the aging stage? The answer: A LOT! Wine aging is a science and has been practiced throughout the wine industry for a long, long time. As wine ages, the chemical compounds within the wine are constantly reacting with each other. These reactions are essential in enhancing the wine’s unique characteristics and qualities.

Chemistry of Aging

Every wine comprises a large variety of chemical compounds. Throughout the aging process, these compounds interact with each other and the surrounding environment. Such chemical compounds consist of acids, alcohols, sugars, esters, and other phenolic compounds. As these chemicals react with one another, the wine undergoes fundamental changes. As a result of aging, most winemakers hope for a series of chemical reactions that will deepen the wine’s flavor and aroma. The amount of time spent in this maturation stage depends on the grape variety, the quality of the wine, and the style and goals of the winemaker.

Oxidization

Oxidation is a crucial aspect of wine aging. Oxidation is a chemical reaction that occurs when air interacts with the wine. As winemakers, we can think of oxidation as our “frenemy”. Every wine needs at least some degree of oxygen to reach its full aging potential. The trouble comes, however, when too much oxygen enters the wine. Finding that perfect balance is essential in ensuring a successful and stable aging period.

Pros and Cons

| Pros | Cons |

| Oxidation can add richness and complexity to a wine’s profile. Most wines are made of a combination of “primary” flavors derived from the grapes and “secondary” flavors from the winemaking process, including aging! Oxidation is a key player in enabling these secondary flavors to form. These secondary flavors can give the wine a more savory, nutty, and earthy feel. Typically, white wines are stored for shorter periods of time to avoid developing those heavier flavors. Lastly, oxidation also helps with color stability in red wines. | This is where the “enemy” in “frenemy” comes in. Although secondary flavors can deepen a wine’s profile, too much oxidation can do just the opposite. To be quite frank, an over-oxidized wine is nothing short of a disaster. Similar to the way fruit rots, too much oxygen exposure can cause the wine to turn an undesirable brown color, severely dull flavors and aromas, and/or promote microbial activity which can lead to a vinegar-like taste and smell. |

Tannins

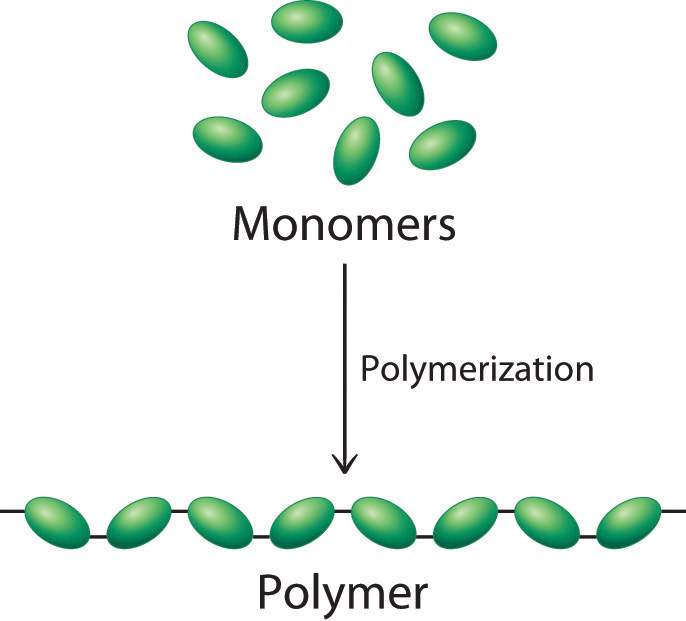

Phenolic compounds are a type of chemical that contributes to the unique taste and smell of food and drink. There are many different types of phenolic compounds found in wine. As wine ages, the phenolic compounds are constantly changing and evolving. Some of the most important phenolic compounds involved in the aging process are called “tannins”. As wine ages, tannins polymerize. In other words, individual tannin molecules join together to create longer chains.

When this happens, the long, polymerized tannin chains sink to the bottom of the wine creating a visible sediment. This process can cause the wine to lose its pronounced flavor and become more mellow and smooth, which depending on the winemaker’s preference, can be appreciated or resented.

However, tannins don’t only bind with each other. They can also bind with other phenolic compounds in the wine, preventing smaller chemicals from evaporating. This process helps to preserve the wine’s primary flavors while also allowing secondary flavors to form.

Sulfur

SO₂ is an extremely important element to discuss when talking about aging. When we say “sulfur” in reference to winemaking, we are specifically referring to sulfur dioxide (SO₂). In today’s world, it is very common for winemakers to use supplemental SO₂ throughout the aging process. The use of SO₂ can affect a wine’s color, texture, and even taste.

Sulfur dioxide is best known for its antimicrobial and antioxidation powers. By preventing an abundance of oxidation and thus growth of undesired yeasts and bacteria, SO₂ acts as a great preserving agent. Since SO₂ acts as an antioxidant, it also helps to curtail the browning process. If the winery is using sulfur dioxide as a preservative, then free sulfur dioxide levels must be monitored throughout the entire aging process to ensure they are at an effective level.

Proper Aging Conditions

In order for wine to age properly, it must be stored in proper conditions. Temperature can alter the aging process. Excessive heat can catalyze undesirable reactions and prevent normal aging reactions from occurring, leading to unwanted changes in taste and appearance. In order to prevent outside variables from disrupting the aging process, it is important winemakers store their wine in specific and stable conditions. Storage tanks are traditionally set at 55°F, allowing standard reactions to carry out while also inhibiting unwanted reactions from taking place. Humidity is another condition to keep in mind; it helps minimize evaporation.

Fun Fact

The earliest evidence of stored wine comes from 7,000 year-old pottery jugs that were buried in the dirt floor of a Neolithic kitchen in Iran. This was considered to be the first ancient attempt at a wine cellar. Thankfully now our systems are much more technologically advanced, allowing us to control humidity, light, and temperature. Just goes to show that even thousands of years later, winemakers are still finding ways to perfect the process.

Penn Museum Object #69-12-15

Oak Barrels vs Steel Vessels

There are a variety of materials used to store wine but the two most common types of vessels when discussing wine storage and fermentation: oak barrels and stainless steel vessels.

Oak barrels allow oxygen to seep through their wooden pores and enter the wine. The secondary flavors that result from this type of oxidation are much sought after in red wines compared to whites. This is why reds are typically stored in oak barrels for longer periods of time, whereas whites are usually kept in steel tanks for shorter periods of time. Typically, winemakers can expect to have 40 mg/L of oxygen enter the barrel for each year of storage.

One of the major downsides of barrel storage is evaporation. In order to prevent this, winemakers should carry out routine topping to minimize the headspace between the wine and the barrel.

Stainless steel tanks prevent any oxygen from getting in. They allow for temperature control, larger volumes, and convenient blending. Unlike oak, stainless does not add any flavor to the wine.

To learn more about oak barrels watch this clip!

Acetic Acid

When winemakers refer to the term volatile acidity (VA), they are referring to the total measure of the wine’s volatile (or gaseous) acids. The primary volatile acid in wine is acetic acid, which is also the primary acid associated with the smell and taste of vinegar. Acidic acid accounts for 93% of the total acid found in wine. Based on what you’ve learned so far, it should come as no surprise that acidic acid plays a significant role in the way wine ages.

Volatile acidity is closely linked to oxidation issues due to an overexposure to oxygen and/or improper SO₂ levels. This is because oxygen is needed by acetic acid bacteria to grow and multiply. As implied by their name, acetic acid bacteria produce acetic acid. Thus, the more acetic acid bacteria, the higher the VA concentration. By limiting oxygen exposure, winemakers can minimize acetic acid content and prevent the wine from developing vinegary undertones.

What can we do in the winery during the cellar aging?

Allow Settling: During the barrel aging process, the acids found in wine combine with lees, pulp debris, tannins, and pigments. As these chemicals join together and grow in size, they tend to sink to the bottom of the vessel. After this sediment has had time to collect, it is removed from the bottom of the barrel, improving clarity. This is particularly important, especially in wines that are not filtered before bottling.

Perform Rackings: This cellar practice removes all the types of microbes that have settled during this time. This process also removes the lees (dead yeast) and other sediment that can be a food source for spoilage organisms.

Stabilization and Fining: If desired, winemakers should utilize this time to create a clean and clear wine through settling, cold stabilizing, bentonite fining, and combining other fining additives.

Monitoring Chemistry: As we mentioned earlier, it is vital to monitor the chemistry during the aging. We recommend sampling each vessel every 4 to 8 weeks, smelling and tasting it, and measuring the free sulfur dioxide levels, the volatile acidity levels, and pH. These metrics can help catch issues early. Do it before it’s too late!

Additional Resources

Maynard, Amerine A. “Aging and Bottling.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/wine/Aging-and-bottling.

“Wine Aging.” Wine Aging – an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/wine-aging.

“Volatile Acidity in Wine.” Penn State Extension, https://extension.psu.edu/volatile-acidity-in-wine.